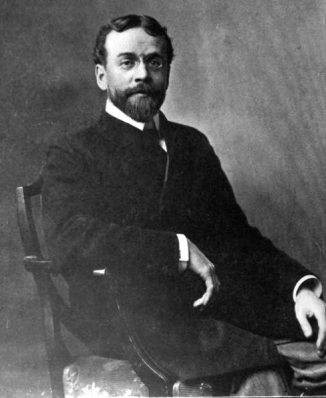

John Colby Abbott, Jr. (1863-1910) was a designer, writer, and public speaker from Boston. He was a key creative force behind the Boston Art Students Association (BASA) and their legendary festivals that energized Boston’s art scene in the early 1890s. He also gave popular lectures on 18th century French fashion that earned him invitations to New York, Paris, London, and the White House.

Abbott was born in Brookline, Massachusetts. His father, John Colby Abbott, Sr., was president of an insurance company, and his mother, Elizabeth Lincoln Abbott, was a counselor and board-member at The New England Hospital for Women and Children.

Abbott was a member of the first class to graduate from the School of The Museum of Fine Arts, and a founding member the BASA, which began in 1879 as an alumni association for the school. In the late 1880s, it began admitting non-alumni as members (Abbott’s Visionist friends Ralph Adams Cram and Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue were among the first) and eventually changed its name to Copley Society.

The group was motivated in 1890 by the unexpected death of a beloved teacher and first headmaster of the school, Otto Grundmann, to raise money to build a studio building in Copley Square in his memory. Grundmann Studios, designed by Cram, , contained two large galleries as well as live-work and work-only studios for rent. Abbott moved in when it was completed in 1894.

BASA members were well-connected in Boston society and their fundraising events were collaborations with their wealthy patrons, who included Isabella Stewart Gardner. Their yearly “Artists’ Festivals”,elaborate and immersive theme parties inspired by the students’ romantic visions of bygone worlds, were the subject of detailed articles, both before and after the events, not only in the local papers but in New York and other US cities.

Abbott had several different roles in the BASA in its early days, but came to be known as the driving force behind their theatrical productions and Artists Festivals. For the 1896 “Arabian Nights” festival, a team or artists led by Goodhue transformed one of the Grundmann galleries into the court of Caliph Harun Al-Rashid. Abbott and Gardner teamed up to costume scores of volunteers who mingled with guests as characters from the world of the Arabian Nights stories. They also held open studio hours in advance of the event for guests who needed help with their costumes, which were mandatory. Abbott, after greeting the high-class attendees in character as the caliph’s son Noureddin, asked them to sit on the floor of the gallery to watch a short play he wrote introducing the court. This was followed by music, dance, and magic acts until 12:15am. According to The Bostonian magazine, “the festival, which had begun with a certain decorum, that might be called Boston reserve … finally eliminated itself, as it were, from the cocoon of moderation into a full-fledge butterfly of innocent, joyous abandon.”

The BASA events seem to have played a major role in bringing together the artists who would form Boston’s bohemia in the 1890s, and this is likely how Abbott got to know Cram and Goodhue. In his autobiography, Cram remembered Abbott as a core member of the Visionists and the source of the costume Herbert Copeland used to officiate as “exarch and high priest of Isis”.

After graduating Abbott worked as an interior decorator and salesman for Shepard, Norwood, and Co., a department store on Winter Street in Boston. In the 1880s and early 1890s, he was active in the Boston theater community as a costume designer, actor, and playwright. His costume design credits included “Tabasco”, one of a series of very popular all-male burlesque operas produced by the First Corps of Cadets to raise funds to build an armory in the Back Bay. He wrote at least two plays that were produced: “A Private Séance” was staged by a repertory company in Helena, Montana. “The Hit”, in which Abbott played a theater owner, was staged in Boston by “The Strollers”, an amateur company affiliated with the BASA.

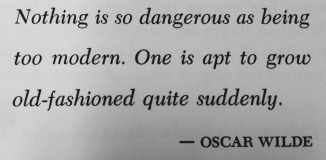

In 1895, Cram’s business partner Charles Wentworth wrote Cram a letter urging him to distance himself from his Visionist friends, especially Abbott, who he said was “rapidly getting a most questionable reputation”. In another letter he compared Abbott to Oscar Wilde, who was arrested for “gross indecency” that year, which suggests Abbott’s “questionable reputation” had to do with being perceived as gay.

In 1903, Abbott married Meribah Philbrick Reed, a poet originally from New Hampshire, in a small ceremony at a friend’s home. They moved to Chestnut St. on Beacon Hill, not far from the Crams.

In the 1890s and early 1900s Abbott gave lectures on cultural history subjects for the BASA and other organizations. His most popular presentation, which he was invited to give at Gardner’s home and those of other society women, was titled “Foibles and Furbelows of the Past”, about the fashions at Versaille in the period leading up to the French revolution. For these talks he used a life-sized cardboard doll he created called “Le Grand Pandore” to model outfits. In 1909 he was invited to present this talk in New York, London, and Paris, and and the White House for an event organized by First Lady Edith Roosevelt.

In the 1900s Abbott served as editor of costume-related photos for the French history book Days of the Directoire by A.R. Allinson. He also had a short story titled “Mamie” published in The Reader magazine.

Abbott died in 1910 at the age of 47. Strangely, though they had mentioned him many times over the years, the Boston papers don’t seem to have published an obituary or any information about his death. Meribah Abbott took over giving presentations with “Le Grande Pandore”, adapting the talk into a regular performance at Keith’s, a Boston vaudeville theater, in 1910. In 1913 she moved to Kittery Point, Maine, where she lived until her death in 1923.

Sources:

* Updated 08/17/2017 with info from the early files of the Boston Art Student Association / Copley Society, from the Smithsonian’s Archive of American Art.

Pelletier, Mabel C., “Festival of the Boston Art Students Association”, The Bostonian, v.1 1894-85, p.354

Oliver, John N., “The Copley Society of Boston”, New England Magazine, January 1905, vol. 31, no.5, p.605

Shand-Tucci, Douglass, Boston Bohemia 1881-1900: Ralph Adams Cram: Life and Architecture, U. of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, 1995

The Boston Globe:

Ad for Shoe and Leather Insurance Co., 05/06/1875 p.5

“Barnet’s Peppery Opera”, 12/31/1893, p.29

“The Hit”, 02/28/1890, p.6

“Fun With The Caliph”, 04/05/1896, p.26

“Table Gossip”, 11/22/1903, p.43

“Famous Doll at Keiths”, 07/06/1910, p.9

“Table Gossip”, 11/13/1913, p.50

“Merry Widow Hats in 18th Century”, The New York Times, 01/05/1909, p.7

“Social Doings of the Week in Paris”, The American Register, London, 05/22/1909, p.3

“News from the Field”, The American Kitchen Magazine, April, 1899, Vol. XI, No.1., p.36

“The Soubrette”, The Daily Independent, Helena, MT, 03/10 1894 p. 6

Oliver, John N., “The Copley Society of Boston”, New England Magazine, January 1905, vol. 31, no.5, p.605

Society Page, The Washington Post, 02/07/1909, p.E6

“Kittery Point”, The Portsmouth Herald, 03/15/1923, p.2

Annual Report of New England Hospital for Women and Children, 1899

History of the New England Hospital for Women and Children, 1899

Clark’s Blue Book, Boston, 1905

Allinson, A.R., Days of the Directoire, John Lane, London, 1910

Abbott, John Colby, “Mamie”, The Reader, Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1904, vol. 4 p.366

Ancestry.com:

1893 JAC Sr. Death Record

1901 JAC Jr. Application for Passport

1910 JAC Jr. Death Record

1903 JAC Jr. & MPR Marriage Record

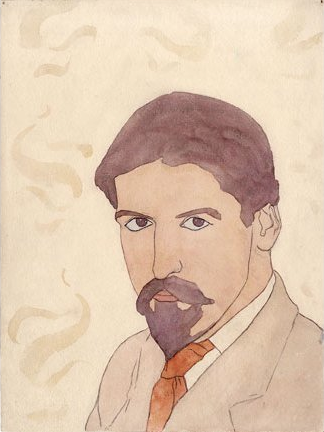

John Colby Abbott in the costume he wore as Noureddin, the Arabian Prince, for the 1896 BASA festival.