Check out the Visionists page just added to Wikipedia!

Tag Archives: bosarts

Photography by F. Holland Day

Images by F. Holland Day: Portrait of Cora Brown, Portrait of Angela Grimke, “Menelek”, “Indian With Jar”, “Orpheus”, “St. Sebastian”, two crucifixion scenes and “The Seven Words”. From The Visionists of Boston documentary.

Boston’s Back Bay, late 19th Century

Boston’s Back Bay in the late 19th century: The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Public Library, Society for Natural History (Museum of Science), and MIT in their original Copley Square buildings, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. From The Visionists of Boston documentary.

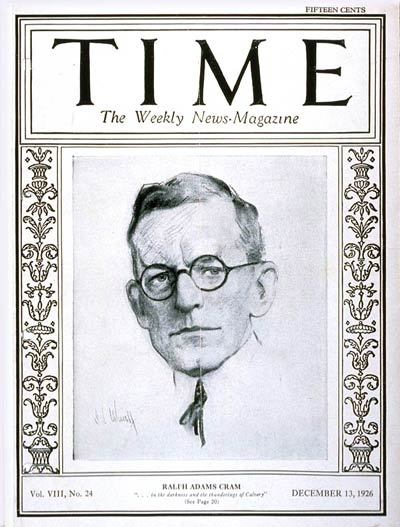

Ralph Adams Cram

Ralph Adams Cram (1863-1942) was an architect and writer based in Boston. He is best known for his churches and public buildings, which include the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York and key buildings on the campuses of West Point, Princeton U., Rice U., U. of Southern California, and others, and both bridges between Plymouth, MA and Cape Cod. The Berkeley Building (aka The Old John Hancock) in Boston’s Back Bay was designed by his firm shortly after his death and pays tribute to the style he established. He also served as Head of the Architecture Department at MIT.

Cram grew up in New Hampshire and moved to Boston to pursue architecture, landing a job at a firm with the help of family friends. He also worked briefly as an art critic for a local newspaper. After winning a small amount of money in an architecture contest, he traveled to Europe with a close friend. This trip had a major impact on him– it inspired his lifelong interest in pre-Renaissance art and architecture, and during his visit to Rome he was inspired to convert to Anglo-Catholicism (ie the Church of England, now better know in the US as Episcopalianism).

One of Cram’s heroes was pre-Raphaelite art critic John Ruskin, who advocated a neo-Gothic approach to architecture, applying medieval principles to modern applications. Cram championed this style in the US, a reaction to the neo-Classical styles he felt had been overused and cheapened here.

In the 1890s Cram was a key figure in Boston’s bohemian scene and a member of the Visionists. During this time he wrote two books he later described as “indiscretions,” both published by fellow Visionists Copeland and Day. Black Spirits and White is a book of ghost stories inspired by his travels in Europe. The Decadent is a dialogue between two Visionist-like characters, one who advocates Christian Socialism and another who argues that Western civilization is in a period of decline (”decadence”) and advocates inaction.

Cram founded an architecture firm in 1889 with partner Charles Francis Wentworth. Visual artist and architect Bertram Goodhue moved to Boston to work for the firm as a draftsman and later became a partner. He also became a member of the Visionists. Both Cram and Goodhue had strong visions of their own, and Goodhue eventually moved on. In 1913 the firm changed its name to Cram and Ferguson.

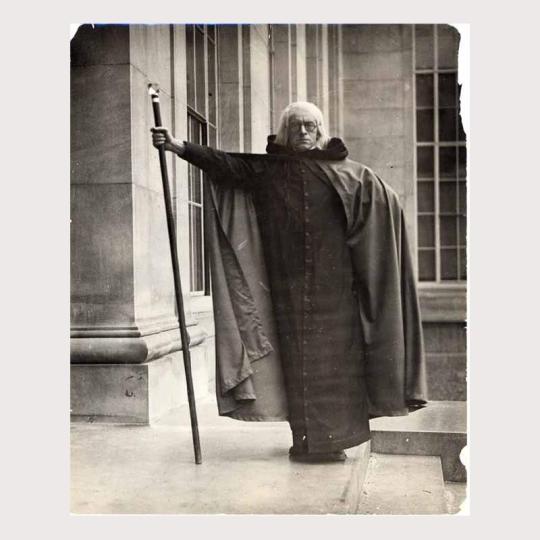

In 1916, Cram masterminded an elaborate pageant titled “The Masque of Power” to celebrate MIT’s move from Boston’s Back Back to its current home in Cambridge. He recruited about 1700 participants in costume and a professional choreographer, and cast himself as Merlin.

Recommended further reading:

My Life in Architecture by Ralph Adams Cram (out of print but check your library)

The Architecture of Ralph Adams Cram and his Firm by Ethan Anthony

Above: Portrait of Ralph Adams Cram by F. Holland Day about 1890. Print in the Library of Congress.

Above: Ralph Adams Cram on the cover of Time magazine, 1926.

Above: Ralph Adams Cram dressed as Merlin for “The Masque of Power” pageant celebrating MIT’s move to Cambridge, 1916. From the MIT Museum.

If you are familiar with MIT you may be familiar with this image which hangs in the “Infinite Corridor” as part of a display commemorating the move.

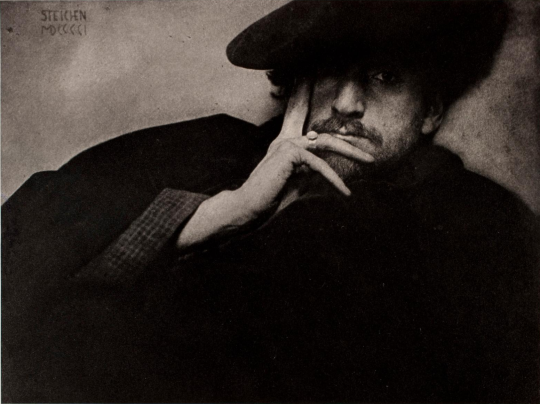

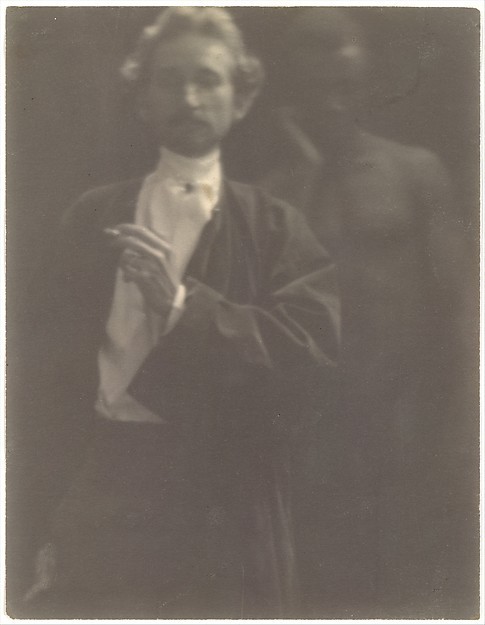

F. Holland Day

Fred Holland Day (1864-1933) was an American photographer and publisher based in Boston who played a key role in establishing photography as a fine art, and served as a mentor to many other artists and photographers.

Day was born to a wealthy family in the part of Dedham, MA that is now Norwood. As a child her was an avid reader and collector, and his hero was English Romantic poet John Keats. (In fact, he helped to organize the fist public memorial to Keats in England.) He attended the Chauncey School in Boston where he met lifelong friend Louise Imogen Guiney. Day and Guiney were part of several literary clubs and artistic circles, including the Visionists.

With fellow Visionist Herbert Copeland, Day founded a small press, Copeland and Day. Inspired by William Morris’ Kelmscott press, they championed quality materials and fine craftsmanship in bookmaking. They were the American publishers of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé and the risqué English journal The Yellow Book.

In time Day’s attention turned from publishing to his lifelong passion, photography. He began taking pictures to document his visits to important literary sites, but came to see photography as artistic expression, drawing inspiration from visual artists. His work included portraits of his many fascinating acquaintances, often in costumes from his collection. He also shot many male nudes, working with professional art models. Much of his inspiration came from classical mythology or religious themes. For his “sacred subjects” series, he re-enacted the crucifixion on a hillside in Norwood, casting himself as Christ and his friends as saints and Roman soldiers.

Day’s bold vision attracted the attention of others working to establish photography as a fine art, including Alfred Stieglitz. At the turn of the twentieth century, Day and Stieglitz were the two best know American photographers. In 1900 and 1901, Day organized a show entitled “The New School of American Photography” in London and Paris which introduced Europeans to several leading American photographers. Stieglitz discouraged associates in London from putting on the show, leading to a rift between him and Day. After that, Day did not include his work in Stieglitz’s influential journals, which perhaps explains why he has not been remembered as well as Stieglitz. A devastating fire at Day’s studio in 1904 destroyed most or all of his negatives and prints. His work now exists in the form of prints in a fairly small number of institutions including the Met, the Library of Congress, The National Media Museum (UK), The Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the George Eastman Museum.

Day’s Universalist upbringing and his experience as a self-taught artist may have instilled in him liberal social values and a strong sense of public service. He was a friend, mentor, or teacher not only to emerging professional artists but to immigrant children in Boston’s South End and at a progressive school for students of color in Virginia. In 1896 he received a letter from a friend who was a social worker in Boston, asking if he might have “any artist friend who would care to become interested in a little Assyrian boy, Kahlil G.” who had shown promise in art classes. Day met with 13-year old Kahlil Gibran, let him help out in his studio, and lent him books from his collection. Not long after, Gibran’s family sent him back to his native Lebanon (then a part of the Ottoman Empire) to continue his education. When he returned to Boston in his twenties, Day hosted the first exhibition of Gibran’s visual art. Through Day Gibran met Mary Elizabeth Haskell, who became his close friend and a key supporter of his work. Best known for his 1923 book The Prophet, Gibran would become one of the best-selling poets of all time.

After the 1904 Day spent less of his time in Boston and more at Little Good Harbor, his beach house in Maine, originally purchased from Guiney. There he focused on photography and hosted some of the many other influential photographers who were his friends or mentees. These included Gertrude Kasebier, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Frederick Evans, Clarence White, Zaida Ben-Yusuf, fellow Visionist Francis Watts Lee, and Edward Steichen. Steichen would become one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century and one of the first fashion photographers.

If you are in New England, a great way to learn more about Day is to visit his former home in Norwood, MA, now the headquarters of the Norwood Historical Society. Check their website for tour information.

Recommended further reading: Through an Uncommon Lens: The Life and Photography of F. Holland Day by Patricia Fanning.

Above: “Solitude,” 1901, a portrait of F. Holland Day by friend and mentee Edward Steichen. Platinum print at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Portrait of F. Holland Day with a male model, 1902 by friend and mentee Clarence White. A platinum print at The Met.

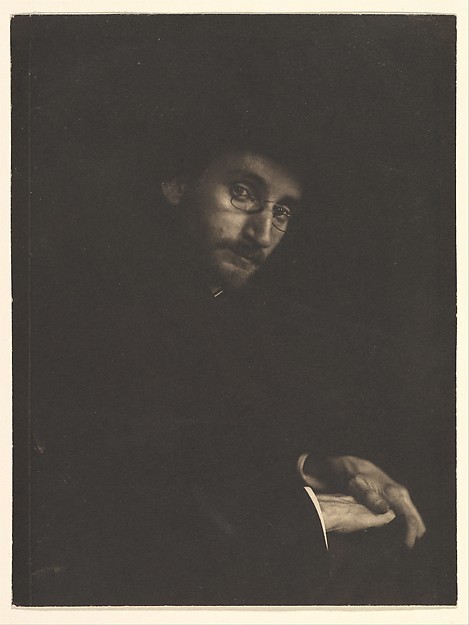

Above: Portrait of F. Holland Day about 1898 by friend and fellow influential pictorialist Getrude Kasebier. Platinum print at The Met.