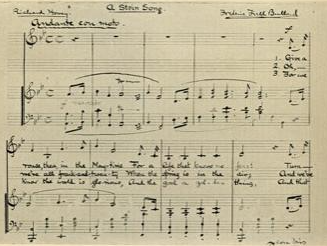

Frederic Field Bullard (1864-1904) was a composer from Boston. He is best known for “A Stein Song”, co-written with fellow Visionist Richard Hovey, which was a favorite on college campuses. (You can hear a recording of “A Stein Song” by contemporary musician Nicole Edgecomb at the end of the “Visionists of Boston” documentary, or a vintage recording from the Library of Congresss linked below).

According to his friend and fellow MIT grad, poet Gelett Burgess, Bullard suffered a spinal injury as an infant which caused occasional pain throughout his life. He was an intellectually curious child who attended the Boston Latin School and then MIT. While studying chemistry as a “special student” he was active in MIT Glee Club performances, playing piano, flute, and double-bass as well as singing. After graduating in 1887, he decided to pursue his musical passion and spent several years in Munich, Germany studying under composer Josef Rheinberger.

Bullard returned to the US in 1892, initially to receive a prestigious music award in New York, then returned to Boston, were he kept himself very busy composing, arranging, and teaching music. He was successful in having several of his pieces published, including “A Stein Song” in 1898, though according to Burgess he never made a living from publishing. In 1896 he married his MIT classmate Maud Sanderson and in 1898 they had a son, Theodore Vail Bullard.

Like his fellow Visionists, Bullard was inspired by the past and by British Romanticism. His published songs included adaptations of poems by Percy Bysshe Shelly such as “Hymn to Pan”. According to Burgess, Bullard was slightly embarrassed to be best know for the “catchy” Stein Song and hoped to be remembered for his more sophisticated compositions. Fellow composer and MIT grad Leo R. Lewis wrote that Bullard was a true musical genius: “I am confident that the concert-giver of the year 2000, making up a programme of a score of the best songs by American composers who were at work in 1900, cannot justly omit a song by Frederic Field Bullard. Nay, more!”

Burgess wrote that Bullard’s associates “were such men as Richard Hovey, Bliss Carman, Ralph Adams Cram, and that little coterie of artists who, first as ‘The Visionists’ and afterward as the ‘Pewter Mugs’, contributed what was most joyous to life in Boston in the 1890’s. With these Bullard, in virtue of his character as well as his talent, was a boon comrade. He was of that ‘Vagabondia’ which gave to the town a new prestige, and he contributed not a little to that frenzied burst of youth which was embodied in ‘Chap Book’ times.” Ralph Adams Cram, who collaborated with Bullard on “Royalist Songs” inspired by Cram’s love of English monarchy, believed Bullard would have been recognized as a genius had he lived longer.

Bullard remained very dedicated to the MIT community, and MIT president Henry S. Pritchett asked him to lead students in compiling the first MIT song book, published in 1903 as Tech Songs: The MIT Kommers Book. In 1904, at the age of 39, Bullard died of pneumonia. Burgess believed that he “literally worked himself to death” preparing music for that year’s Tech Reunion event. Bullard and his family had recently moved from Boston to Scituate, Massachusetts (also home to Thomas Meteyard).

The “Stein Song” remained a staple of MIT Glee Club performances, including “pops” concerts at which the club performed with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. It came to be considered MIT’s Alma Mater song (although the lyrics did not reference MIT) and freshmen were instructed to stand and remove their hats whenever they heard it. It was also a favorite at Dartmouth College (Richard Hovey’s alma mater) and Tufts University (where Leo Lewis taught). Lewis included it in a 1915 Tufts song book re-titled as “Campus Song” with lyrics slightly altered to refer to Tufts. In the 1920s, MIT held a series of contests for a new alma mater song to replace the “Stein Song,” in part because its drinking theme became more controversial during Prohibition. The attempts to change the song were not popular among students and alumni, and none of the winners caught on easily. “Arise Ye Sons of MIT” by 1926 alum John B. Wilbur is now described as “MIT’s closest thing to an old alma mater”.

Manuscript of “A Stein Song” from the MIT Archives.

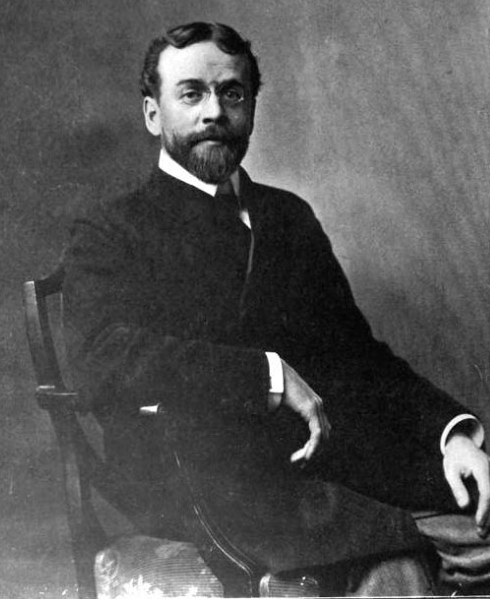

Frederic Field Bullard c1904, unknown photographer, from Technology Review

Vintage Recording of “A Stein Song” by Frederic Field Bullard and Richard Hovey from the Library of Congress

Vintage Recording of “Beam From Yonder Star” by Frederic Field Bullard and William Prescott Foster from the Library of Congress

Sources:

“Bullard: The Man” by Gellet Burgess and “Bullard: The Musician” by Leo R. Lowry, Technology Review, January 1904, pp. 586-601

Tech Songs: The MIT Kommers Book 1903 page by MIT Archives

Crams, Ralph Adams, “My Life in Architecture“, Little, Brown, and Company, 1936

The Boston Globe:

“Boston Men Win Prizes in Music”, April 1, 1893

“Composer Laid at Rest”, June 29, 1904

“Tech Wants a New Song—Stein Song Too Painful”, February 26, 1922

The Tech:

“Must We Be Collegiate?”, March 4, 1928

“The Need for A Song”, January 9, 1925

Wikipedia (stub page only in German so far)